Daydreaming

“Guard well your spare moments.

They are like uncut diamonds.

Discard them and their value

Will never be known

Improve them and they will

Become the brightest gems

In a useful life.”

Table of Contents

1. Daydreaming and mind-wandering.

2. Understanding daydreaming.

3. How is daydreaming useful?

4. Can daydreaming be used intentionally?

5. How can we deploy daydreaming to maximum effect?

6. What are the conditions for effective daydreaming?

7. What does this mean for School?

8. Conclusion.

Daydreaming and mind-wandering

“Daydreaming” comes with a lot of baggage: perhaps “Mind-Wandering”, with its evocation of freedom, exploration and taking a walk without a destination captures the potential better. It is a bit like Meditation, but different in this particular sense: Meditation focuses your thoughts on the actual, Mind-Wandering imagines the possible. Meditation invites Presence, a deepening sensitivity to what is; Mind-Wandering sends you off to imagine what is not, but could be.

For the more practical among us, that is what makes it so easy to condemn. Mind-Wandering is pure fantasy. It also seems to sneak up on you in the middle of something else, making it disruptive instead of productive. You start listening to a lecture about climate-change, and your feral mind soon has you canoeing the Amazon. It seems to threaten learning rather than support it. It is embarrassing to be caught in a “cognitive control failure”, but one study shows we may spend almost half of our waking hours in reverie (Killingsworth, 2010, p. 932). How could it be, from an evolutionary perspective, that we spend so much of time on something seemingly problematic and unprofitable? What is the benefit?

Writer Amy Fries asks:

“Are we denying some aspect of our humanity by trying to banish our daydreaming natures? We wouldn’t have art, invention, philosophy, progress, or spirituality without it. The ability to imagine is the key to invention, problem solving, and discovery.”

We need to distinguish mind-wandering that impedes learning from mind-wandering that offers a learning experience. In other words, when is “wasting time” not . . . wasting time?

Understanding Mind-Wandering

Dr. Jerome L. Singer, Professor Emeritus of Psychology at Yale University (1924-2019) studied mind-wandering for 60 years (though he preferred the term daydreaming and I will use the two term interchangeably). Singer differentiated three types of daydreaming (McMillan, 2013, p.5):

1. Positive Constructive Daydreaming (PCD): playful, future-focused, imaginative thought.

2. Guilty Dysphoric Daydreaming (GDD): full of obsessive, anguished fantasy.

3. Poor Attentional Control (PAC): inability to focus on anything you’re thinking or doing.

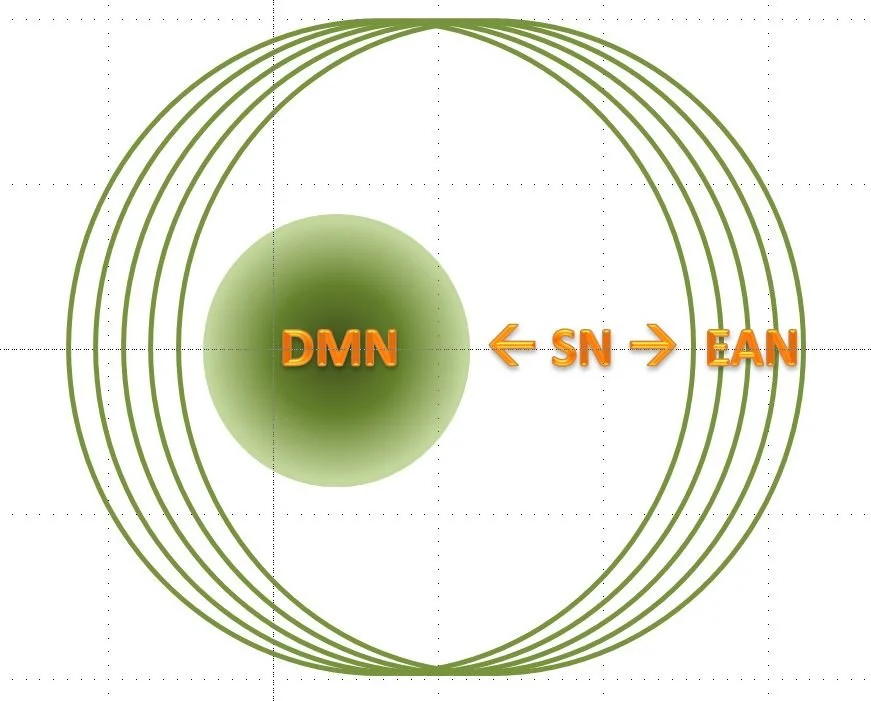

Forgive me a paragraph of jargon, but this model of how we pay attention is interesting. We have in our heads as humans, a baseline level of cognitive function in a Default Mode Network (DMN) to which we revert when our Executive Attention Network (EAN) relaxes or shuts down. The EAN keeps us outwardly focused: on tasks and environmental awareness, our cell phones, our proscribed tasks, that tiger in the bush. The DMN has us inwardly focused: on ourselves, on our future and on making meaning. When the EAN cedes exclusive control, when we are safe and “take some time for ourselves”, we can experience “perceptual decoupling” (we largely cede environmental awareness) and “meta-awareness” (we become conscious of our thoughts). A third network, the Salience Network (SN), negotiates between the DMN and the EAN.

How is Daydreaming useful?

Singer showed that daydreaming happens under the DMN, when we focus inwardly. He found evidence that it can yield profitable results as Positive Constructive Daydreaming:

“For the individual, mind wandering offers the possibility of very real, personal reward, some immediate, some more distant. These rewards include self-awareness, creative incubation, improvisation and evaluation, memory consolidation, autobiographical planning, goal driven thought, future planning, retrieval of deeply personal memories, reflective consideration of the meaning of events and experiences, simulating the perspective of another person, evaluating the implications of self and others’ emotional reactions, moral reasoning, and reflective compassion.”

The rewards of Positive Constructive Daydreaming fall into four broad categories:

“Future planning which is increased by a period of self-reflection and attenuated by an unhappy mood; creativity, especially creative incubation and problem solving; attentional cycling which allows individuals to rotate through different information streams to advance personally meaningful and external goals; and dishabituation which enhances learning by providing short breaks from external tasks, thereby achieving distributed rather than massed practice.”

Dishabituation helps you remember what you learn, Creativity and Attentional Cycling are mechanisms that foster invention and improve problem solving, and Future Planning points to an exploration and extrapolation of self. If Positive Constructive Daydreaming (PCD) can be controlled, and Guilty Dysphoric Daydreaming (GDD) and Poor Attentional Control (PAC) avoided, then PCD appears indeed rich in learning potential.

Consider:

Are you permissive or punitive about mind-wandering in the classroom?

Could you help your students to manage their mind-wandering and control their attention?

Can Daydreaming be used intentionally?

Singer did indeed suggest that Daydreaming can be volitional: that we can learn to do it intentionally and effectively. We can learn to manage our Salience Network and control our consciousness: whether we be outwardly or inwardly focused. The literature on this remains largely anecdotal however, and dips heavily into neuroscience:

“Most likely, volitional daydreaming involves the interaction of multiple large-scale brain networks. For instance, . . . the ability to generate and sustain an internal train of thought is supported by cooperation between the EAN and the DMN. Another important player is most certainly the salience network (SN), which includes the anterior cingulate cortex, presupplementary motor area, and anterior insulae. The SN is important for the dynamic and flexible switching between the EAN and the DMN. Since the SN plays such a crucial role in signaling the need to change streams of consciousness, an inability to activate the SN might not only lead to difficulty with cognitive control, but may also limit the ability to access a positive and constructive inner stream of consciousness on demand. ”

Thus while literature and the popular imagination might consider Daydreaming as something that sneaks up on you when you’re bored, this need not be the case: Daydreaming can be deployed as a tool to achieve the potential benefits. In practice this means teaching your students to synchronize the Executive Attention Network (EAN) and the Default Mode Network (DMN), the former to yield control and the latter to support Daydreaming with intention.

Consider: How might you develop a script to engage your students in their own mind-control?

How can we deploy daydreaming to maximum effect?

How to take advantage of Daydreaming depends on your goal. If future planning is on your mind, you might find benefit in some version of the Zander letter, named after conductor and music teacher Ben Zander. Zander promised every student an “A” in his classes at the New England Conservatory of Music if they would write him a letter dated the end of the semester explaining what they did to deserve it. The more detailed the letter the better, since it forced students to consider the hurdles they would overcome as well as the outcome they imagined. Daydreaming proves most effective when it pre-imagines the process as well as the result.

If creativity is your goal, two brainstorming sessions separated by 12 minutes of daydreaming greatly improves the innovation in the second effort. A study at the University of California at Santa Barbara used 145 undergraduate students to show that after brainstorming uses for mundane objects, 12 minutes of daydreaming greatly expanded their ability to list additional uses afterwards (Baird, 2012)

If retention is of utmost importance, than take note of the pause. From Spaced Learning (Brandon, 2020) we understand that a 10 minute pause between intense 20 minute exposures to new material tremendously improves retention, with 3 exposures and 2 pauses the recommended discipline. The key is to insure that the cognitive activity during the pause is completely different from the learning exposure, like daydreaming.

How do we intentionally daydream? One recipe proceeds as follows:

“To start PCD, you choose a low-key activity such as knitting, gardening or casual reading, then wander into the recesses of your mind. But unlike slipping into a daydream or guilty-dysphoric daydreaming, you might first imagine something playful and wishful—like running through the woods, or lying on a yacht. Then you swivel your attention from the external world to the internal space of your mind with this image in mind while still doing the low-key activity.”

That prescription was intended for a professional audience, but the basic approach is clear: disengage your mind by engaging your body, set an intention, and then let your thoughts drift! By putting these tools at our student’s disposal, and offering them the time to employ them, we are literally teaching them how to think.

Anne Isabella Thackeray Ritchie (1885) coined the adage “Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish and…”. By teaching students to think in this way, do we not perform a similar service?

What are the conditions for effective Daydreaming?

Daydreaming doesn’t happen usefully under duress. A 2015 study (Seli et al, 2016) suggests that mind-wandering occurs as often during easy tasks as challenging tasks, but that it skews towards more intentional mind-wandering during easy tasks and unintentional mind-wandering during difficult tasks.

Intentional Daydreaming, in other words, requires the mental space to deploy it. In fact, researchers caution that the increasing pressure on students to stay externally focused, by staying on task academically or monitoring communications on cell phones, not only impairs their ability to focus inward, but by doing so, actually impairs their ability to focus outward. Humans function best neurologically when we toggle back and forth between inward and outward focus. Mary Helen Immordino-Yang explains the implications for school:

“Consistently imposing high attention demands on children, either in school, through entertainment, or through living conditions, may rob them of opportunities to advance from thinking about “what happened” or “how to do this” to constructing knowledge about “what this means for the world and for the way I live my life.”

In other words, if we don’t give students a break, we short-circuit the cycle of learning posited by Dr. Barry Kort at the MIT Media Lab. We eliminate the processing required to make meaning out of facts. We substitute volume of information for wisdom.

Consider:

Knowing that your students need the time to toggle between inward and outward focus, how might you help them to structure their day?

What kind of institutional changes might be required to support students in this way?

Effective Daydreaming can’t be taken for granted however. Just giving students time to relax does not ensure that they use the time to build connections between their inner and outer worlds. In fact, an unnerving study (Wilson, 2014) showed that the majority of people would rather hurt themselves than be left alone with their thoughts:

“Many people seek to gain better control of their thoughts with meditation and other techniques, with clear benefits. Without such training, people prefer doing to thinking, even if what they are doing is so unpleasant that they would normally pay to avoid it. The untutored mind does not like to be alone with itself.”

In Wilson’s study, participants given a choice between submitting to a painful electric shock or simply sitting quietly to think…chose the shock. It remains to be seen if it was the isolation or the thinking, or the thinking in isolation, that triggered the response.

What does this mean for School?

Neuroscience and the study of Daydreaming offer a specific prescription for structuring school: Balance.

“Educational experiences and settings crafted to promote balance between “looking out” and “looking in,” in which children are guided to navigate between and leverage the brain’s complementary networks skillfully and in which teachers work to distinguish between loss of attentive focus and engaging a mindful, reflective focus, will prove optimal for development. Put another way, leaving room for self-relevant processing in school may help students to own their learning, both the process and the outcomes. ”

Humans learn best when given the opportunity and environment to toggle between outward and inward focus. This simple conclusion offered to us by 60 years of psychological investigation and now neuroscience serves as a powerful indictment of the status quo. When is there time for intentional daydreaming in a classroom singularly focused on the next exam? Where is there space for inward attention in a high school schedule of 50 minute classes and 6 minute classroom cycling? What opportunity is there for individual meaning-making in a school where you are never alone and ever outwardly vigilant? The very structure of 25-30 students kept constantly on-task or interacting, whether in class, at recess or in study hall, and then sent home to stay focused even there, suggests little to no time at all for building deep, emotional connections between our inner and outer worlds. We need to be far more intentional about teaching our kids to nurture those connections.

What is the right amount of time for inward and outward focus? What is the rhythm that works best for consolidating learning or realizing the other benefits of daydreaming? Another way to approach this question is to ask what the attention span might be for our students. Despite unsubstantiated claims that our attention span is now less than that of a guppy, Neil Bradbury (2016) points to student motivation, teacher charisma and enthusiasm, variety in the learning experience and graphic quality (a good picture is worth a thousand words) as variables that determine attention spans. The folk wisdom about 8 second or 15 minute attention spans is nonsense according to Bradbury. The admonishment for teachers is to be aware of your students and bring flexibility, variety and enthusiasm to the encounter.

Conclusion

School serves our students best when it offers both pedagogy and pause, when pedagogy adopts pause. Because the structure of 50 minute classes and 6 minute transitions doesn’t offer students a chance to relax in the Default Mode Network of their minds, and the pressure to test and perform can be overwhelming, it is absolutely vital that students learn effective daydreaming and that teachers structure their classes to support it. Daydreaming, intentional mind-wandering encouraged in students given the time and space to connect their outer and inner worlds, can play an important role in the Cycle of Learning. A waste of time and an obstacle to learning only when it is left to sneak up on us randomly, we can teach our students to deploy it as a tool to enhance creativity, improve retention, imagine the future and plot a path, and build personally relevance: meaning.

From the account of August Kekulé, the German chemist who in 1862 imagined the circular structure of the Benzene molecule in a reverie and from there developed his “Theorie uber die Constitution des Benzols”:

“If we learn to dream, gentlemen, then we shall perhaps find truth —- To him who forgoes thought, Truth seems to come unsought; He gets it without labor. ”

This book was birthed on the premise that students should do as much as think. It finds equal sustenance now for an argument to not-do.

References

Baird, B., Smallwood, J., Mrazek, M., Kam, J. W. Y., Franklin, M. S. & Schooler, J. (2012, August 31). Inspired by Distraction: Mind Wandering Facilitates Creative Incubation. Psychological Science. pp. 1117–1122

Brandon, B. (2020, January 10). Designs That Work: Spaced Learning. Learning Solutions. https://learningsolutionsmag.com/articles/designs-that-work-spaced-learning

Fries, A. (2009, July 01). The Great Paradox: Daydreaming vs. Mindfulness. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-power-daydreaming/200907/the-great-paradox-daydreaming-vs-mindfulness

Immordino-Yang, M. H., Christodoulou, J. A. & Singh, V. (2012). Rest Is Not Idleness: Implications of the Brain’s Default Mode for Human Development and Education. Perspectives on Psychological Science 7(4) p357, DOI: 10.1177/1745691612447308, http://pps.sagepub.com/content/7/4/352

Killingsworth, M.A., & Gilbert, D. T. (2010). A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science 330. DOI: 10.1126/science.1192439

McMillan, R. L., Kaufman, S. B. & Singer, J. L. (2013, September 23). Ode to positive constructive daydreaming. Frontiers in Psychology 4(626). DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00626 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3779797/pdf/fpsyg-04-00626.pdf

Pillay, S. (2017, May 12). Your Brain Can Only Take So Much Focus. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2017/05/your-brain-can-only-take-so-much-focus

Ritchie, A. I. T. (1885). Mrs. Dymond. Smith, Elder & Co.

Schooler, J. W., Smallwood, J., Christoff, K., Handy, T. C., Reichle, E. D. & Sayette, M. A. (2011). Meta-awareness, perceptual decoupling, and the wandering mind. Trends Cogn.Sci. 15, 319–326. DOI: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.05.006. Meta-awareness, perceptual decoupling and the wandering mind - PubMed (nih.gov)

Schultz, G. (1890). Bericht uber die Feier der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft zu Ehren August Kekulé’s. Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft.

Seli, P., Risko, E. & Smilek, D. (2016, March). On the Necessity of Distinguishing Between Unintentional and Intentional Mind Wandering. Psychological Science 27(5), DOI: 10.1177/0956797616634068

Wilson, T. D., Reinhard, D. A., Westgate, E. C., Gilbert, D. T., Ellerbeck, N. Hahn, C., Brown, C. L. & Shaked, A. (2014, July 4). Just think: The challenges of the disengaged mind. Science 345(6192) p75 https://wjh-www.harvard.edu/~dtg/WILSON%20ET%20AL%202014.pdf

Your thoughts on this journal post are highly valued, as I continue to build and refine my perspective on schools and the school environment. Please share your own experiences and perceptions of the school environment below!